Large program evaluations often include very large, complex data collection activities. Khulisa has conducted quite a few large surveys over the years, both in-person, electronically, and otherwise. We’ve also gained valuable experience conducting household surveys, which require a different design and strategy to surveys conducted at service delivery points.

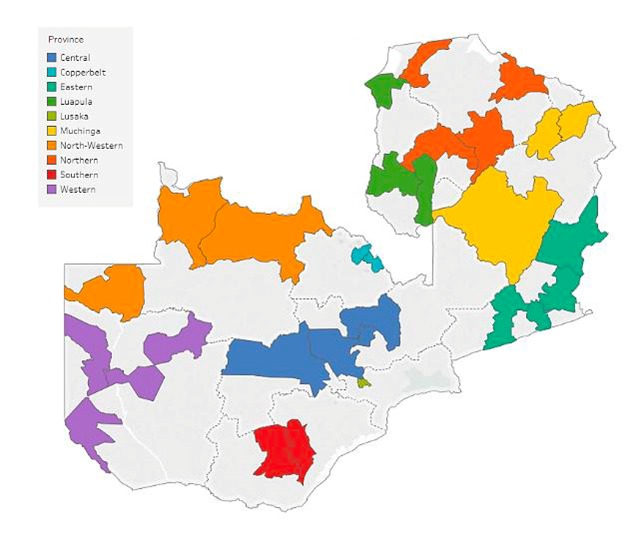

Since 2019, Khulisa has been working on a multi-sectoral nutrition study of households in Zambia. The study involves planning and implementing baseline, midline, and endline surveys of 7,500 households in 30 districts, dispersed across all 10 provinces in Zambia. The surveys comprise hundreds of questions on more than two dozen indicators and include health questions and measurements for women of child-bearing age and their small children.

To protect the respondents in this survey, Khulisa received Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval for the surveys and ensured a detailed informed consent from household respondents prior to initiating the interviews. The midline survey included drawing finger-prick blood samples, which required an on-site health professional and oversight by local health agencies.

Sampling for the two rounds of household surveys was complex and involved working closely with districts and local communities. “In every district, we selected ten enumeration areas using probability proportionate to size, which means the more populous enumeration areas were more likely to be selected,” said Mary Pat Selvaggio, Khulisa’s Director of the Health Division. “Then in each enumeration area, we created a list of all households with children under two years of age, which we obtained from the community chief or the community leader. And then from the full list, we randomly selected 25 households. In each selected household, the mother or the primary caregiver was interviewed and various body measurements and blood samples of both the mother and the child were taken.”

Key Lessons for Population-based Household Surveys

Zambia is a country of nearly 300,000 square miles, with diverse terrain and many remote, hard-to-reach areas. Teams were in the field collecting data for more than eight weeks, armed with tents, generators, and solar batteries, and contending with bad weather, impassable roads, large distances within and between enumeration areas, and many other challenges.

Here are some of the most important things we’ve learned while conducting this ambitious survey.

- Rigorous recruitment, training, and supervision of field workers is essential.

When implementing large population surveys over a huge geographical area, it is essential to hire experienced field workers, train them well, and provide regular, hands-on supervision. Our recruitment process focused on selecting candidates with prior experience with large surveys, as well as the necessary language skills to communicate with respondents in their own language.

Training involved several rounds of assessments to weed out less-than-capable candidates. Candidates who had successfully completed the training were deployed in teams of five, with one supervisor per team to ensure constant quality checks on the data generated. Furthermore, our team put in place extra layers of quality control, in the form of quality controllers and a survey manager, to decrease the likelihood of incomplete or inconsistent data.

“It’s a very, very intensive process…and there are lots of places where things could go wrong,” Edna Berhane, the project’s Quality Improvement Advisor, said. “Even with rigorous training, in the field setting [the supervisors] were able to pick up things that needed to be corrected, such as the way field workers were translating the questionnaire into the local language and not giving communities/households specific days for data collection once listing and household selection was completed (thus necessitating call backs), among others.”

- Communication, communication, communication.

The Khulisa team ensured that good and consistent communication was an integral and critical component of carrying out the household surveys. “We sent letters to the provinces and districts, alerting them that the baseline and midline [survey] was going to happen, what it entailed, and what level of cooperation was needed from them, etc.,” said Edna. “We understood the importance of making sure that lack of communication to the districts or provinces didn’t become a barrier [to conducting the surveys].”

- It’s important to work with, and listen to, local communities.

Conducting a household survey, especially a survey involving health, is a sensitive, intimate experience that requires a lot of engagement, buy-in, and time from families and communities. While conducting the baseline survey, the Khulisa team recognized the importance of working with chiefs/community leaders to ensure the teams were welcomed in each community. In some cases, Khulisa discovered it was necessary to offer small honorary payments or gifts to communities as a show of courtesy or good faith.

“It didn’t even occur to us to do it previously, but we realized that it is the culture. And [the small gifts] enabled the opening of doors and the receptiveness of the community to have us come in and do the data collection,” Edna explained. “It’s the importance of community-level engagement, not necessarily on our terms, but on theirs.”